Brandon Chow |

Why Most Investors Will Never Get a 100-bagger

Have you ever gotten a 100-bagger? It’s an elusive question that most would like to admit to, but unfortunately, fall short as they look through their personal trading accounts and realize they are nowhere close.

Do these mysterious 100-baggers exist? How do you get one? I’ll save you the reading. In short, it’s holding a great, small company for a really, really, really long time.

But what do we need to look for? Finding a great company to invest in, especially in the microcap stage, is only part of the story. Holding onto it through the ups and downs is the bulk of the challenge and also means not giving into commonly espoused mentalities such as “selling your winners to buy others (hopefully not losers)” and “taking profits.”

In fact, as we comb through the data, we start to see that the average investor is getting further and further away from ever achieving the elusive goal of a 100-bagger.

This presents a unique opportunity for those who are or are willing to become the antithesis of the broader market. Patient, long-term investors who have high conviction and, again, want to hold their stocks for a really long time.

Note to readers

While 100-baggers have been discussed in the past, including in Thomas Phelps’ 100 to 1 in the Stock Market, there hasn’t been any spotlight on Canadian listed and/or headquartered success stories. This article will attempt to bring those names to the forefront and help Canadians better understand the formula for investing in upcoming Canadian 100-baggers.

I’m not here today to discuss how to stock pick a great microcap investment. I’ve written previous articles on this, and it will also be addressed in future content. Today’s article will focus on the data I’ve gathered to illustrate the power of conviction and patience.

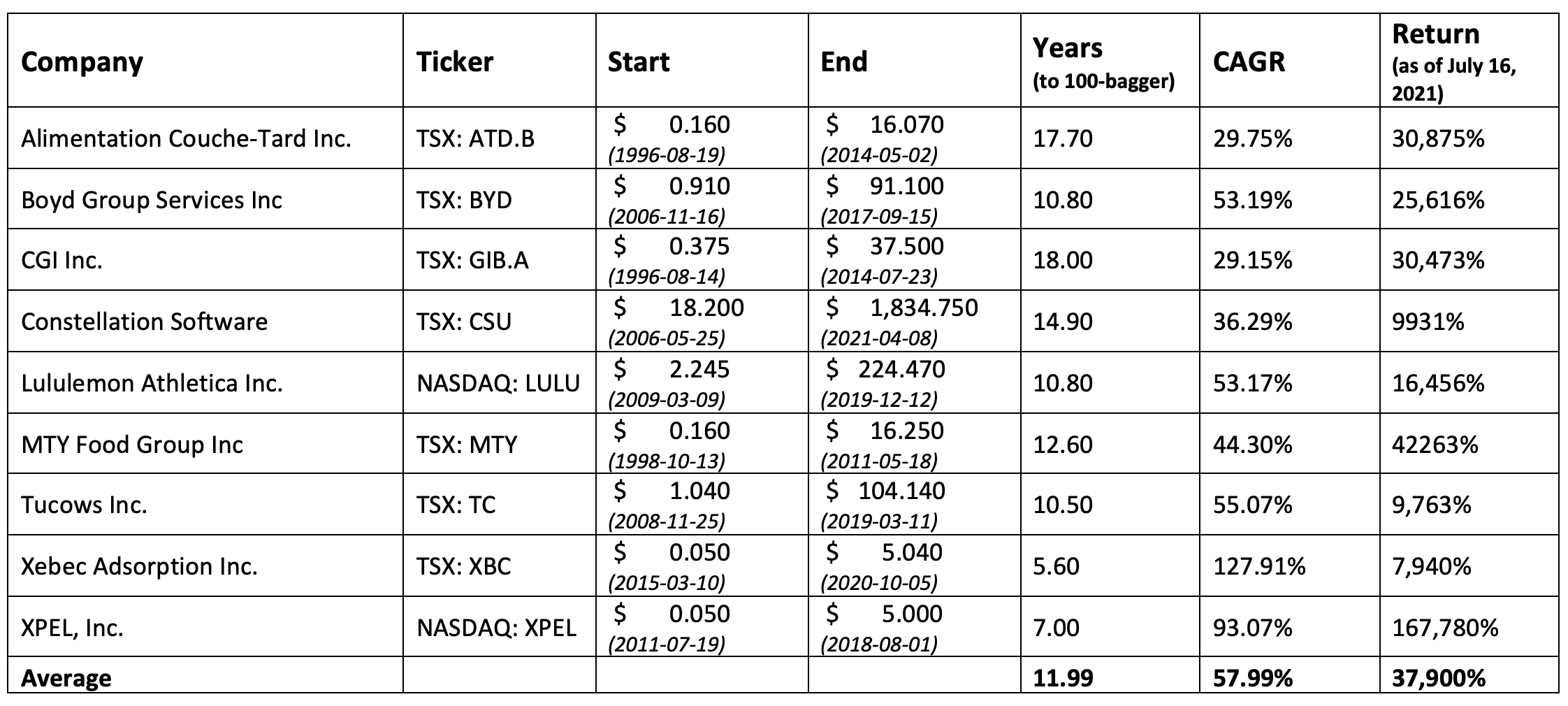

Sample List of Canadian 100-baggers

Below is a list of Canadian-themed 100-baggers which shows the company name, ticker, and a starting price which is an all-time low for the stock. The subsequent columns show the end date in which it achieved 100-bagger status, the amount of time it took to achieve that, the compound annual growth rate (CAGR) over the time frame, and return from the starting point to July 16, 2021. The returns do not include dividends.

We can infer from this table that time invested is an important factor in realizing a 100-bagger and helps these companies achieve their high-sought-after status. With an average duration of 11.99 years and an average CAGR over that time frame of 57.99%, the compounding over the years is impressive.

Why might it be so hard to get a 100-bagger? We investigate that now.

However, before we dive into it, I’ve also included a list of honorable mentions which haven’t achieved 100-bagger status yet and are well on their way.

Honorable Mentions

- CCL Industries Inc. (TSX: CCL.B)

- Dollarama (TSX: DOL)

- Enghouse Systems Ltd. (TSX: ENGH)

- goeasy (TSX: GSY)

- Pollard Banknote (TSX: PBL)

- Shopify (TSX: SHOP)

1. Most investors don’t invest in microcaps

All of the 100-baggers listed above used to be microcaps (<$500 million market cap) at their starting price. Small companies have the ability to grow quicker, but by conventional finance definition are higher risk which translates into higher volatility.

According to the Wilshire 5000 Total Market Index, large caps represented approximately 92% of the total U.S. equities market as of December 31, 2020. The majority of investors would rather invest in large-cap names because they are perceived to be more stable, more transparent, and offer certainty through quarterly dividends.

However, large caps face the law of large numbers.

“The law of large numbers tells investors that companies with a small market capitalization have much more room to grow (at a much faster rate) than companies with large market capitalizations.” Source

Therefore, you cannot get a 100x return if you are investing in a company that is already too big. All 100-baggers in our sample list (except for Constellation Software) started as penny stocks (under $5.00 per share).

2. Most investors don’t hold long enough

We’ve already established above with our sample set that the average time it takes to get a 100-bagger is at least a decade. Does the average investor have the patience to see it through?

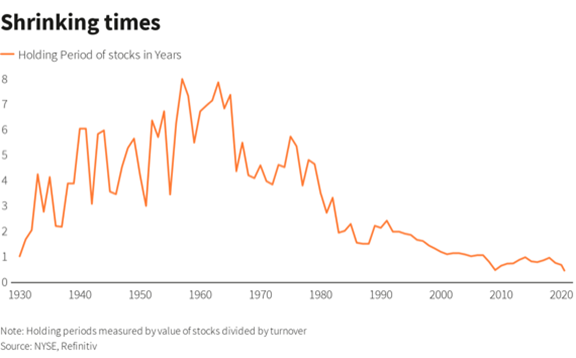

According to Reuters, who used data from NYSE and Refinitiv, the average holding period for stocks is now under a year. The chart below shows the shrinking hold times for stocks, which has been on the decline since the 1970s and continues.

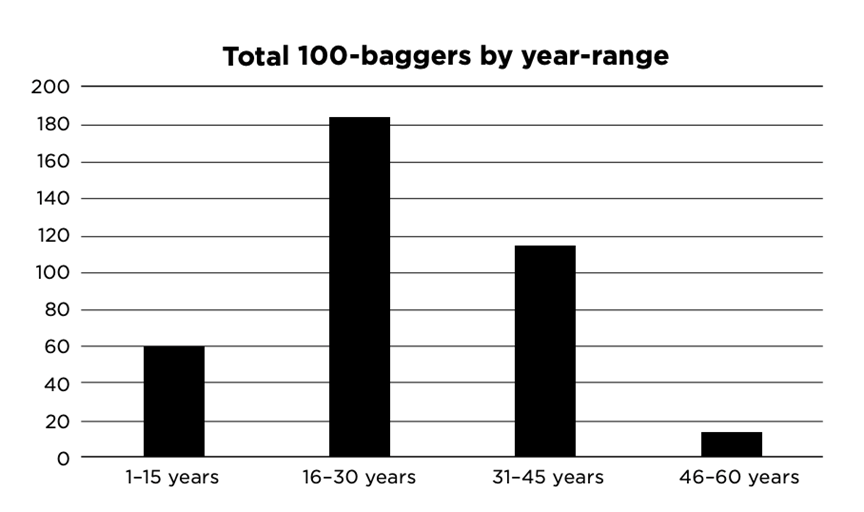

Furthermore, in Christopher Mayer’s book titled 100 Baggers: Stocks that Return 100-to-1, he analyzed almost 400 U.S 100-baggers and charted the time it took by year-range. In his analysis, the majority of 100-baggers took between 16 and 30 years!

Investing for the long-term in the 21st century has become more difficult for several reasons: ease of trading, being bombarded with information constantly, and higher volatility.

The reality is that investors are becoming increasingly further off from achieving consistent, market-beating returns by not being invested for the ultra-long term.

3. Most investors struggle to battle against convention

The thought of a 100-bagger may be overly ambitious for some, and I am sure investors would be thrilled with doubling, tripling their money. Given profits along the way, there are many temptations to sell according to “conventional wisdom,” which can force you to exit part of or your full position before even getting started.

For example:

- As soon as you double, sell half of your position, making the rest of your position “risk-free.”

- Selling your winners to buy more of underperforming losers.

- Divesting of your position when the stock “goes up too much” and passes its fair valuation.

Stocks are subject to swings in share price, and in the short term, there will be fluctuations that will create a temptation to buy and sell. However, a lot of this can be noise and force you out of a position that, over the long term, will continue to perform well and look consistent on a 10 to 20-year timeframe.

“Our Favorite Holding Period Is Forever.” – Warren Buffett

Warren Buffett’s timeless quote of a forever holding period holds true to the data supporting ultra-long-term investing. Warren recommends that if we do not feel comfortable owning a stock for ten years, then we should not even hold it for ten minutes.

It turns out that at least ten years is what it is going to take.

Conclusion

The theory behind successful investing is not rocket science and has been well documented for more than a century. However, in practice, it’s hard to battle our own emotions, stay true to our commitment to investing in tiny companies and hold them for a really long time.

At the end of the day, it’s a game of psychology that has become increasingly more difficult to play as we operate in a world with rapid information, emotion amplified by social media, and fast money coming in and out of the next hot area.

There are many great Canadian microcaps waiting out there. Ones that I hope to report on in 10 to 20-years, that we will discover, invest into and hopefully reap 100-bagger status from.

Best of luck. Long and Strong.

About The Author

Brandon Chow is your financially savvy millennial whose microcap portfolio was kickstarted from a six-figure exit of his IT hosting company in high school. Full-time, he is fighting climate change by leading investor relations at Xebec Adsorption (TSX: XBC), a leading Canadian cleantech company. He also aims to educate and inspire millennials to build a deliberate life by investing in their version of “YOLO” through The YOLO Fund.

Disclosure

Espace MicroCaps contributor Brandon Chow owns shares of Xebec Adsorption (XBC.TO) and is employed in investor relations by the company.